Yesterday I made a banana cake out of bananas that we felled. I say “felled” because that is how you harvest bananas, the whole (pseudo)stem coming down with a rope and a machete. After the adrenaline of the act, we each broke off and ate one, short and fat, dense, sweet, somewhat slimy (in a great way), and oh so warm. Imported Ecuadorian-grown Cavendish bananas will never taste the same again.

We’ve started to make our way home, and have spent the last week and a bit volunteering with Shirin and her urban food forest in the centre of Johor Bharu, in Malaysia.

Once we’d packed up for the day, Shirin sawed the huge bunch of bananas into “hands” and we delivered them to some of the neighbours. The rest we packed into the baskets of our bikes, and cycled them slowly, precariously, home to watch them ripen on the porch.

[Fun banana facts: a single banana is called a “finger”, what we call a “bunch” is actually a “hand”, and a full cluster, as they grow, is called a “bunch”. The “trunk” is neither a trunk, nor a stem, but a “pseudostem”, as it is just a tight packing of the lower parts of the leaves.]

I’d heard about the insecurity of Cavendish bananas, the type we eat, but felling my first (non-Cavendish) banana pseudostem made me want to go back to understand it properly.

What an odyssey.

This seemingly simple question has been a gateway to a truly eye-opening ride through fruit breeding, global politics, trade agreements, biodiversity, and our rights to food.

I started reading, and then kept reading, exploring thread after thread. I got obsessed with bananas and how they are teaching me so many lessons about the world, and it has taken over my intellectual space and almost all my free time for the last week.

I know many of you who read what I write will be well-versed in these ways of our world. I feel like I am just starting. I’ve been having many conversations recently about how to exist, and what to do, in authenticity, in a world that feels so broken. Diving into this reading and thinking has been one way, for the last few days at least, to see the power behind the haze, and speak to it. This reading and writing really has been a journey.

Maybe get a cuppa, if you’re keen to journey with me.

You may know that export-quality Cavendish bananas, the ones we eat, are predominantly grown in Ecuador, the Philippines and Costa Rica on monocropping banana farms. You might also have heard that the global supply of Cavendish bananas is at high risk of being wiped out. But why?

BECAUSE ALL THE BANANAS WE EAT ARE STERILE.

Wild bananas are full of seeds. There are thousands of types of them, and most of them are not particularly tasty. But because we humans don’t like to eat seeds, the particular bananas we eat were chosen because they don’t have them. They don’t have seeds, and therefore they are manually reproduced by dividing the rhizome of one plant and replanting the pieces, like what you do when you propagate a peace lily. All the Cavendish bananas in the world, therefore, are genetic clones of one another. They’re identical, almost devoid of genetic diversity*. Because of this, there is very little ability, naturally or otherwise, to develop resistance to disease or adaptation to changing climates through a random genetic mutation that might otherwise happen whenever the plant produces a seed. With this, they are exceedingly vulnerable to disease. A disease that can kill one Cavendish banana plant, can kill them all.

But what’s the big deal? Countries that grow bananas, like Malaysia, have heaps of different types they grow and eat, right?

Though the bananas we harvested this week are delicious, they ripened within days, and bruised easily. And like the Cavendish, these “edible” varieties are also all sterile, without seeds, and perhaps more critical to the export question, have lower yields and don’t travel well. And they can’t be bred to travel well. Because they have no seeds.

Cavendish bananas account for 99% of banana exports to developed countries and 47% of global consumption. So unless you live in Malaysia, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Uganda, Rwanda, the Philippines,…. unless you can actually GROW a banana where you live, it’s possible our banana-for-breakfast days will soon be over.

Until the 50s the precursor global export banana was the Gros Michel, and from what I read, it was a vastly superior banana to our beloved Cavendish. The Gros Michel was also sterile, and because of this, coupled with the dense monocropping that is characteristic of banana plantations, they were functionally wiped out by the Panama disease soil fungus in the 1950’s. A disease that can kill one of the clones will kill them all. Fast.

The only way for international corporations to continue to grow bananas for export in places infected with Panama disease was to abandon the infected land and buy up more, fresh, land.

In Guatemala, the largest landowner in the country in the 50’s, greatly enabled by corrupt Guatemalan dictators, was the United States’ United Fruit Company (now rebranded as Chiquita Brands International). In order to reduce income inequality, the president of the time, Jacobo Arbenz, passed land reforms that expropriated this unused, Panama-diseased land back to the state with compensation, and gave it to poverty-stricken, landless Nicaraguan peasants who could then work the land with other crops, meanwhile improving exploitative Guatemalan labour practices. Unhappy with this and presumably its effect on their bottom line, the United Fruit Company duly went and lobbied President Eisenhower, who quickly labelled Arbenz as a communist and a “threat to democracy”. (The Secretary of State of the Eisenhower Administration, John Foster Dulles, was also a Board member of the United Fruit Company.) Under “Operation PBSuccess”, the CIA then proceeded to pour weapons into the country to arm a group of angry right-wing civilians, and used fake radio broadcasts and warplanes to drop bombs across Guatemala to incite panic in the population. They drove the 1954 coup that deposed Arbenz and his democratically-elected left-wing government. The CIA then installed the pro-business government and military regime of Carlos Castillo Armas to prevent and roll back reform. This coup caused violent political instability that lead to the almost 40-year Guatemalan civil war, characterised by a string of right-wing military dictators and the Guatemalan Genocide of Maya Indigenous populations. The Ixil Mayas; the Q’anjob’al and Chuj Mayas; the K’iche’ Mayas of Joyabaj, Zacualpa and Chiché; and the Achi Mayas were all genocided (Holocaust Museum Houston, n.d.). The government of the United States of America has never apologised. This corporation has since rebranded.

And this is only one story.

A corporation losing profits, through its government, manufactures violent political instability in a foreign country.

A corporation, not a country. Oh wait, is a corporation a country? No, hang on. Is a country a corporation?

I apologise, I’m getting confused…

Back to our beloved Cavendish banana.

To combat the very real threat of fungal disease, lest over $8 billion dollars of export profit be compromised, Cavendish bananas are sprayed HEAVILY. The Cavendish banana is the most heavily sprayed food crop in the world.

This doesn’t seem to affect us as consumers of the bananas (bananas are closer to the “Clean 15” than the “Dirty Dozen”), but it is debilitating to the lives and health of the plantation workers, their children and their unborn children in these developing countries.

Women in banana packing plantations in Ecuador, where most of our bananas come from in New Zealand, suffer from leukemia and birth defects at twice normal rates.

The banana industry typically applies mancozeb—a fungicide of rising scientific concern due to a slew of health effects—up to 90 times a year. In the US, the EPA recommends a minimum 24-hour wait before re-entry into a field aerially treated with mancozeb to protect workers. Premature re-entry has been linked to tumors, birth defects, cell mutations, and thyroid mutations. It is of particular concern for pregnant women because it can negatively impact the brain development of the fetus. Unfortunately, researchers in Costa Rica have discovered that pregnant women living closest to banana plantations have higher exposures to the fungicide due to nearby aerial applications.

(Global Health Now, 2020)

Banana plantation workers are getting really f*ing sick.

In 2018, 1,200 Nicaraguan former plantation workers took Dow Chemicals, Shell Oil, and Occidental Chemicals to court in France for making them sterile, after these companies continued to promote and use a fungicide, dibromochloropropane aka Nemagon, in Nicaragua for years after it was banned in the United States. Workers had tried to sue these companies in courts in the United States but Dow and Shell blocked the lawsuits on the grounds the damage hadn’t occurred on US soil. The workers then appealed to Nicaraguan courts, and in 2006, were awarded $805 million in damages from these three companies. The companies, however, refused to pay, Shell claiming that their headquarters were in the United States and that they had no employees in Nicaragua. So these workers then tracked these companies’ assets to France, and attempted to force the payouts through French courts. In 2022 they were once again denied the compensation.

Many have since died. None were ever able to father children.

I don’t think I’ll ever look at a banana the same again.

So we’re happily eating our delicious, nutritious bananas at a massive cost (noting, though, that organic bananas do not pose these same risks to plantation workers). And changing focus from this direct human cost for a moment, our over-reliance on these seedless fruits is having a devastating effect the biodiversity of our food sources, and, therefore, on global food security.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) estimates that about 75 per cent of the genetic diversity of agricultural crops has been lost in the last century due to the widespread abandonment of genetically diverse traditional crop landraces in favour of genetically uniform modern crop varieties.

(WWF et al., 2006)

Through climate change, habitat destruction and subjugation of indigenous peoples who caretake much of the the world’s biological diversity, often for the purposes of claiming or clearing the land for monocropping itself, the diverse genetic bases of all these different food plants are being destroyed and we are being opened up to huge local, and global, food insecurity.

Monocropping for export, for yield, for taste and texture, for profit, for feeding a booming population, is pushing out and taking over the growing of traditional seed varieties, and centralising food production in really dangerous ways.

Here in Malaysia, small-holding and indigenous farmers and farming communities are fighting new legislation that will ban un-registered collecting, re-use, on-selling and sharing of seeds. This is the move to implement International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV 1991) as a part of a trade agreement with European Free Trade Association.

In Asia and Latin America, 70-80% of farmers’ seeds are saved seeds from previous years, and in Africa, this figure is up at 80-90%.

What happens when you legislate away a practice that is not only generations old, or centuries old, but that has existed since the birth of agricultural communities over 10,000 years ago?

What happens to peoples’ abilities to feed their communities?

The Convention was first drafted in 1961 and has been revised three times (in 1972, 1978 and 1991), each time to strengthen the rights of corporate breeders and restrict what others can do with the seeds. The 1991 revision was particularly controversial because it eliminated the right of farmers to save privatised seeds and also limited what other plant breeders can do with that seed.

For most of its history UPOV has been a small and rather obscure club of mostly rich countries that wanted to advance the interests of their seed companies.

At the time of the last revision, 1991, only 20 countries were members. But after the World Trade Organization agreed in 1994 that all WTO member countries should have intellectual property rights for plant varieties, UPOV membership quickly increased and over 70 countries are members today. Much of this was due to arm twisting by rich countries to get non-industrialised countries to sign on, like through the trade agreements.

(Grain, 2015a)

Ostensibly, this is to protect the rights of plant breeders to continue to sell their seeds and “recoup” their seed breeding costs. With seeds now commonly being bred overseas and imported into a country, these laws and regulations can also protect farmers from bad quality or diseased seed batches. In practice, however, the over-reach that is hidden in the fine print and increasingly aggressive wording and opaque legislative processes is forcing small-scale, local food producers into an unsustainable reliance on repeatedly purchasing seeds controlled by governments and corporations, and breaking thousands of years’ old traditions of food production that preserve genetic diversity, resilience and adaptive capacity to climate change, cultural traditions and people’s rights to food.

In some countries, farmers can keep certain privatised seeds for reuse in the next season on their own farms, but the extent to which this is permitted differs between countries: from being allowed, to having to pay royalties back to the seed producer, to being banned outright. To reuse these seeds with permission generally requires large amounts of disclosure and bureaucracy, stating on which fields you will plant and how much, and be open to inspections from public and/or private entities.

However, even if a farmer only the uses wild or indigenous seeds that they have used for centuries, avoiding all modern varieties, these indigenous seeds can be taken by breeders, reproduced and improved somehow, and then privatised. Going way further than that, breeders are then allowed to expand their rights, from the privatisation of their improved seed to all varieties similar to it, due to snakey wording about what “previously known” or “a matter of common knowledge” means, and to whom. If an indigenous species is “common knowledge” to generations of local farmers, but not to the market, it may be classed as “new” and, therefore, it is open to be claimed by a breeding company. Farmers will then find out that they cannot use their own saved, indigenous seed unless they pay royalties to the company that privatised them.

Social movements and peasant farmer organisations around the world have been mobilising to protest these changes in their countries for decades.

And yes, I have looked to see if New Zealand is party to this convention, and yes we are. We signed up to the UPOV in 1981. The full, controversial UPOV 91 amendment was a part of the highly protested Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (I remember marching down Lambton Quay for these protests), and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership that New Zealand did sign in 2018 required us to either accede to the UPOV 91 or to implement a Plant Variety Rights Act that is consistent with it.

In 1991, the WAI262 Treaty claim was submitted to the Waitangi Tribunal. This pan-iwi (pan-tribal) claim covered, among other things, critical issues of misappropriation and misuse of mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) in research, the protection of native flora and fauna, and cultural intellectual property rights, in relation to the rights and responsibilities of Māori and the British Crown which are enshrined in our founding Treaty, Te Tiriti o Waitangi. In 2011, the Waitangi Tribunal’s response to this claim, the Ko Aotearoa Tēnei report, was finally released, which made four recommendations in relation to the Plant Variety Rights Act. After a period of review, “strongly informed” by UPOV 91 and Ko Aotearoa Tēnei, our government finally passed the updated Plant Variety Rights Act in 2022.

I do not have the expertise to understand what this really means for iwi, hapū, rural communities or small-scale farmers (and there is not much written about it), but it feels like it’s really important.

What MBIE themselves say on their page about these amendments to the Plant Variety Rights Act feels shady to me, which I guess is what happens when an amendment to law is of the “give” rather than “take” part of a trade agreement.

Aligning with UPOV 91 may encourage investment in New Zealand’s plant breeding industry, as well as the importation of new varieties into New Zealand. However, strengthening plant breeders’ rights needs to be balanced against the interests of farmers/growers, Māori, consumers and other interested groups, to achieve a net benefit to New Zealand as a whole.

(MBIE - Background to the Plant Variety Rights Act review, 2022)

It’s unclear if this “balance” has been reached, or, more importantly, if the Te Tiriti responsibilities of the Government to protect Māori rights to tino rangatiratanga have been upheld, or if these two things are even compatible. The language of “strengthening plant breeders rights” balanced against the “interests of Māori” suggests they are not. What we do know is that Te Tiriti o Waitangi and WAI 262, to whatever extent they were applied, have offered some protection for all New Zealanders and our shared environment, plants and animals as this review has taken place.

There is so much more to this, but I am already getting a “post too long for email” warning. The more I read, the more I am learning about trade agreements, political-economic power, the loss of global biodiversity, farmers rights movements and the impact of UPOV 91 in different countries. I am but barely skimming the surface of topics that are peoples’ life’s work, and communities’ intergenerational work.

My eyes are being opened to the fact that it is money, rather than ethics, that drives global (and often, national) politics, and teaching me to look underneath the label of a “humanitarian crisis” or “war-torn” country, and critically consider the causes of the crisis, or the war.

With the biodiversity crisis, the climate crisis, the continuing wholesale slaughter in Gaza + apartheid regime in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, international claims on natural resources that are fueling war in the Sudan and and exploitation of the people of the Democratic Republic of Congo, again and again the world over, and the terrifying, anti-democratic moves of our own Government right now, I feel like these links are becoming clearer. And we need to be making them.

From bananas, to it all.

From the money to the seed laws, to the wars, to the breakdown of our natural world and our relationship to it. And back again.

I will leave you, if you managed to get to the end of this tale, with the inspiration that originally shook me, and helped to see these links and write about them.

And then I will offer some suggestions for some things we can actually do.

Because solidarity is a goddamn verb.

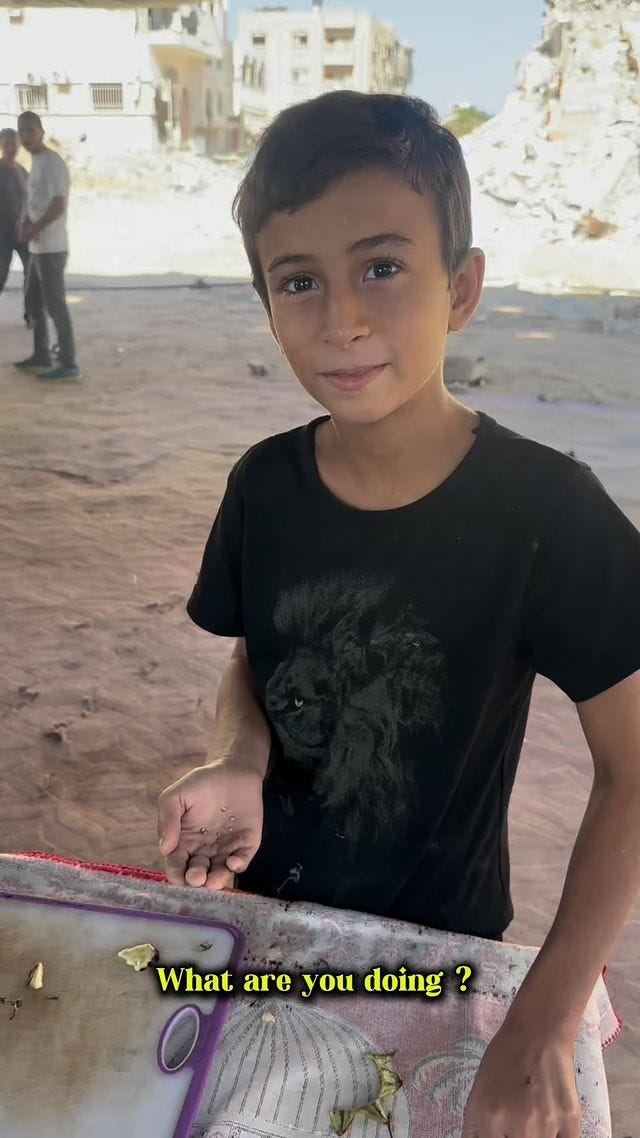

This child in northern Gaza, where fresh food is almost non-existent right now and the people are facing a forced starvation, is saving seeds from a smashed tomato and is growing seedlings, to grow tomatoes, to feed his people.

The things we can do, now:

We can buy organic, Fair Trade bananas, that are not sprayed with the same carcinogenic, sterilising, life-altering substances as non-organic bananas, and are more likely to pay plantation workers fair wages. Exploring this world of bananas has also doubled down my intention to avoid imported produce as much as possible, and buy local.

We can think twice about buying fruit that is seedless; seedless watermelon, seedless grapes, seedless mandarins are also genetically identical to one another, like bananas.

These struggles are all connected. Te Tiriti o Waitangi protects us all, and The Treaty Principles Bill was introduced today, almost two weeks before it was planned. We can spend some time to understand the Toitū te Tiriti movement and the Treaty Principles Bill, and look into supporting, or joining, the hīkoi which is starting next week in the Far North to and arriving at Parliament on the 19th of November.

It’s all about the money. If you haven’t yet signed the petition to pressure ASB bank to divest from Motorola Solutions (see my previous post if you missed it), that is profiting off the Israeli regime which is evicting Palestinian peasant farmers from their land, has criminalised the organisation maintaining the Palestinian seed bank and made foraging for staple, traditional Palestinian foods illegal, you can do this quickly and easily, here: https://our.actionstation.org.nz/petitions/don-t-bank-on-apartheid-asb-kiwisaver-divest-from-illegal-israeli-settlements-or-we-switch

Looking for seeds for your summer garden? Diversify your food, try some cool new veges and check out the Koanga Institute, who have been saving and protecting heritage seeds in New Zealand for the last 30 years; they’ve got wonderful vegetable and flower seeds and fruit tree seedlings, many of which you may have never come across before! This Red Orach, perhaps, or this Dalmation Cabbage?

And finally, does anyone want to do a foraging workshop with me? Let’s learn together about the nutrient-dense, free foods that just exist around us. Message me if keen!

*I say “almost devoid of genetic diversity” because if you grow enough bananas, eventually one will have a genetic mutation that throws a seed. By “enough”, I refer you to an experiment where scientists grew 30,000 identical banana plants and hand pollinated them every day for a year with pollen from a wild, fertile banana variety. They got 440 tons of fruit, and after sifting through all this fruit, they found only 15 seeds…and only four or five of them germinated.

If you want to read one thing about the wild world of bananas, I recommend this one. It’s what started me down this long and winding exploration.

The Conservation Magazine, 2008. The Sterile Banana, by Fred Pearce. https://www.anthropocenemagazine.org/conservation/2008/09/the-sterile-banana/

Other sources drawn on:

Global banana trade facts and general banana histories:

https://www.fao.org/economic/est/est-commodities/oilcrops/bananas/bananafacts/en

https://globalhealthnow.org/2020-03/deadly-side-americas-banana-obsession

Epicurious, 2023: Bananas Don’t Taste Like They Used To. Here’s Why, by Brandon Summers Miller. https://www.epicurious.com/ingredients/history-of-the-gros-michel-banana

The Conservation Magazine, 2008. The Sterile Banana, by Fred Pearce. https://www.anthropocenemagazine.org/conservation/2008/09/the-sterile-banana/

The 1954 Guatemalan coup:

CNN, 2011: Apology reignites conversation about ousted Guatemalan leader, by Mariano Castillo. https://edition.cnn.com/2011/10/22/world/americas/guatemala-arbenz/index.html

Holocaust Museum Houston, 2024: Genocide in Guatemala. https://hmh.org/library/research/genocide-in-guatemala-guide/

Wikipedia, n.d.: Guatemalan Civil War. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guatemalan_Civil_War

Wikipedia, n.d.: Banana republic. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Banana_republic

Nicaraguan plantation workers’ court case:

New York Times, 2019: Sterilized Workers Seek to Collect Damages Against Dow Chemical in France, by Liz Alderman. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/19/business/energy-environment/dow-chemical-pesticide-banana-workers.html

Bangkok Post PCL, 2022: Nicaraguan plantation workers 'poisoned' by pesticides fight for justice, by AFP. https://www.bangkokpost.com/world/2309610/nicaraguan-plantation-workers-poisoned-by-pesticides-fight-for-justice.

UPOV 91, seed laws and the threat to our food systems:

AgNews, 2019: Asian NGOs raise concern over intellectual property and seeds in RCEP Trade Deal. https://news.agropages.com/News/NewsDetail---29517.htm

Consumers Association of Penang, 2024: Lack of recognition of farmers’ rights by Malaysian government is worrying, by the Malaysian Food Sovereignty Forum. https://consumer.org.my/lack-of-recognition-of-farmers-rights-by-malaysian-government-is-worrying/

GRAIN, 2015a: UPOV 91 and other seed laws: a basic primer on how companies intend to control and monopolise seeds. https://grain.org/en/article/5314-upov-91-and-other-seed-laws-a-basic-primer-on-how-companies-intend-to-control-and-monopolise-seeds

GRAIN, 2015b: Seed laws that criminalise farmers: resistance and fightback, by La Via Campesina. https://grain.org/en/article/5142-seed-laws-that-criminalise-farmers-resistance-and-fightback

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE), 2022: Background to the Plant Variety Rights Act review. https://www.mbie.govt.nz/business-and-employment/business/intellectual-property/plant-variety-rights/plant-variety-rights-act-review/background-to-the-plant-variety-rights-act-review

WWF, Equilibrium and University of Birmingham, UK, 2006: Food Stores: Using protected areas to secure crop genetic diversity, by Sue Stolton, Nigel Maxted, Brian Ford-Lloyd, Shelagh Kell, and Nigel Dudley. https://awsassets.panda.org/downloads/food_stores.pdf

Israeli attacks on Palestinian food and seed sovereignty:

Haaretz, 2021: On Israeli Defense Minister's Target List: The Palestinian Seed Bank, by Amira Hass. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/2021-11-08/ty-article/.premium/on-israeli-defense-ministers-target-list-the-palestinian-seed-bank/0000017f-dede-db22-a17f-feff92eb0000

Undark, 2020: For Israelis and Palestinians, a Battle Over a Humble Plant, by Shira Rubin. https://undark.org/2020/02/10/akoub-israel/

Visualizing Palestine, 2022: Israeli Restrictions on Palestinian food sovereignty affect every item on this table. https://visualizingpalestine.org/visual/food-sovereignty/

I knew a little of this story, but not the full extent. thank you for this work - and all of the links/suggestions!