The scents that remember, and the smells you want to forget

with Daphne Odora, by Sandra Turner, and a wander through Alaskan times

This post is a personal indulgence of words and story, visual images and video. For a time when you can sit, explore, and hopefully, enjoy x

Note - the imagery is best viewed in landscape, either on a laptop, or your phone rotated.

The smell of the cancer day unit makes my throat thick.

Activates my gag reflex. Requires a subtle swallow. It makes me grumpy and irritated. Through my last regime the memory of the smell lodged in my throat so that even before I’d arrive, the irritation would set in.

Smells are special in the way they spoon themselves so tightly to memories. They are visceral and specific, triggering vivid rememberings of moments or places long forgotten by the conscious mind.

It turns out that is because the brain’s olfactory bulb, or “smell centre”, is a part of the limbic system, physically close and directly connected to the hippocampus, responsible for memory, and the amygdala, responsible for emotional processing. It’s not coincidental that smells incite in us such emotionally evocative memories.

Yearning to smell

The year before mum died was distinctively both full and devoid of smell. I lived in Alaska doing my PhD; a project I loved, in a place I could not. Fairbanks, Alaska was frozen from October to May, and I arrived in September. With a deep coating of fluffy snow, sub-negative-20 temperatures and the driest of dry air offering the most striking of snowflakes, smells hibernated until melt season.

I studied sea ice, the ice that forms on the surface of the ocean, in Kotzebue, a small village in a large sound on Alaska’s north-west coast. The first time I went on the ice I was stunned, and sad, that I couldn’t smell the ocean. I was deftly told that “the smell of the ocean was really just the smell of seaweed”. This was a blunt, and plainly evident reckoning of one of my first lessons in the ways of this different world.

I was also doing a course in Traditional Ecological Knowledge. One of the assignments was to spend one hour a week over four consecutive weeks outside in a spot with no human influence. The task was to merely observe, and then to note your observations and the evolution of your observations once you came back in. This was a challenge in the snow-laden Alaskan interior where I lived. To be away from human influence required skis, or lots of knee-deep trudging. My first week I wrote extensively:

To the west were the rolling hills of the Alaskan interior; sepia grey, burgundy and white, depending on the spruce, birch or snow that covered its surfaces. It is to this direction I first placed myself, defined by the fierce wind at my back. This wind would be, in any other place, a breeze. It was slow. The trees and the leafless shrubs were only shivering as it passed. But it was most certainly a wind, here. It is not the speed, but the feeling, that defines your name for this thing. Only my eyes were available to feel its sting, and they quickly obliged.

I wrote about observing the landscape through my New Zealand-trained eyes, the new habit of analysing the snow for wind stress and avalanche potential, and meditating on the far away hills to understand the meaning of the “snow line”.

When I first observed the tree line on the Alaska Range, my instinct told me that this was the snow line. A moment later I was able to recalibrate my observation to the rules of this new land. The “snow line” has no meaning here; the partition between black and white is one of surface growth, not temperature.

I wrote about the sting of the air, what I saw in the valleys of the hills, and how I heard running water in the the sound of the breeze.

What was absent in what I wrote: any observation of smell.

I missed smells so deeply without realising it.

I remember the smell of the entryway of the Geophysical Institute: the space between the automatic doors, two sets of them to keep the heat in. It was where the remnants of not-yet-kicked-off snow from your boots would fall and melt, soaking into the carpet. This area was perpetually damp. And it was here that I took some privacy to talk to my brother, pacing, as he told me with love that April, that “mum and dad are trying to protect you from the hard stuff, but I think you should know — mum was talking about how she wanted her funeral to be. There was a gathering at home. She talked through what she wanted.” The dampness smelled like the forests of home, the mist-laden air of New Zealand bush, and the soaked soil. I was desperately homesick, and desperately heartsick.

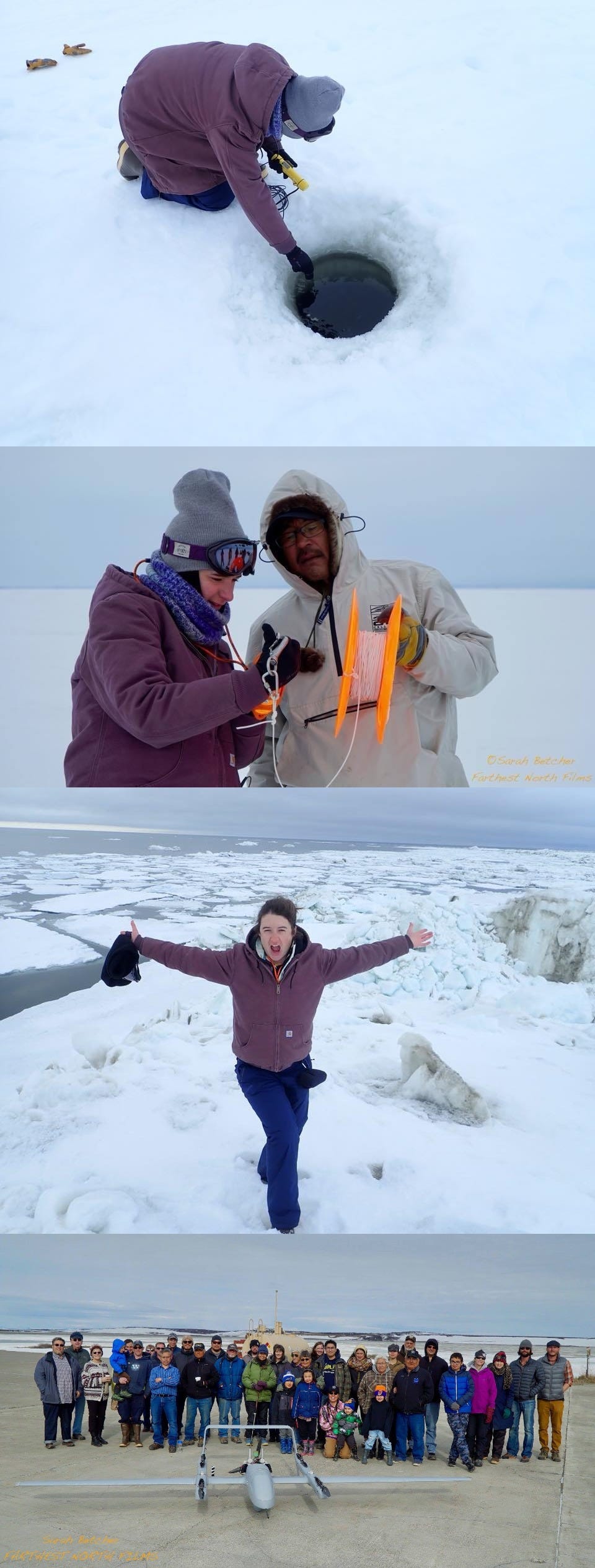

I spent a month on and off the ice in Kotzebue for my field work during April and May, and attended a field camp in Utqiaġvik, the northernmost settlement in the United States, at a latitude of 71°18' N. This time had a fierce protection around it, by mum and dad shielding me from the worst of what was happening with mum’s health back home, and by the exhilaration and excited focus of what I was doing: on the sea ice every day with Iñupiaq elders being gifted stories of ice and life, slaying the snow machine across miles of frozen ocean, eating muktuk and akutaq and going sii fishing.

And the science, of course!

When I finally flew back to Fairbanks to unpack, pack again and head home to visit — mum’s aspirational family trip to Hawai’i having turned into “it’s better if you come home”, having turned into “it’s better if you come home and make sure you have a flexible ticket” — I stepped off the plane and onto a damp runway. During my time up north the melt had started, and only the shaded corners were still frozen.

The melt had started.

I was shocked, as I drew in the precious wet air, the ecstasy of the aroma of wet concrete reaching entirely inordinate levels.

There were smells again.

When I got home to my dry cabin, I stood in the forest and smelled. For ten minutes I just stood there and breathed in the scents of the dirt, and the trees, and the grubs and the critters and the moose droppings that had started to inhabit the air again.

I didn’t know how much I had missed the smell of the earth, even that I had missed the smell of the earth, for so long. *(see endnote on “Wilderness”)

The smells of home

The smells of home are distinct, and life giving, and coming home to Dunedin offered new types of smells.

Mum loved flowers that had a fragrance.

A cruel dupe, she would say, is a rose without a scent.

The roses at the gate of our family home were carefully chosen to delight those walking in, and those at the door to her office were strategically placed to offer her lush sensory moments between clients.

While she was in hospice a friend brought her a sprig of daphne odora. She was sedated, but I like to think her favorite fragrance soothed her in her rest. I’ll let her tell you about daphne odora in her own words below.

Being the end of July we also had small bunches of early cheer daffodils with us, the little tufts of sweet mid-winter goodness that get you through the short days to the warming rays of spring. I like to think of them as the mandarins of the flower world. Sweet and, for me at least, always somewhat unexpected offerings that appear during the depths of the grey to lift my spirits.

After this time, I was given the gift of moving in with an old school friend. She had a bunch of essential oils, and I got hooked on jasmine oil. I would rub it on my wrists and neck, and sniff it like an addict to get a hit of the fresh, floral life that I had been missing for so many months in Alaska. Jasmine oil is known for its calming and uplifting effect on the nervous system. Evidently, my nervous system of 2018 knew what it needed.

Late last year I tried to plant a daphne odora in the pot beside mum’s gravesite. We wanted a plant to beautify the spot, and a fragrant plant, a Daphne, seemed just right to me. So off I went to the local garden centre to get one, lovingly tuck it up in its soil bed and drop it around the road at her gravesite beside the lagoon. It promptly died. Dad has since replaced it with pansies, and their prosaic yet tasty leaves are currently being ravaged by slugs. I kind of like this. It just shows you can’t be too bloody sentimental about it all.

I have planted early cheer bulbs in our garden though, and they have already poked their little heads out of the dirt, getting ready to welcome us into spring.

We’ve also planted a jasmine climber, a gift from my Aunty. Mohamed chose the plant after smelling all the varieties on offer, because this one reminded him of home in Lebanon. It is outside our office, with the hope that it will climb up and offer us whiffs of joy during the work day. He’s brought me outside a few times already, to share in the delight of the fragrance her few flowers are putting out.

Making my own choices

Smelling my jasmine oil the other day triggered me to do something about my time in the cancer day unit. I now have a menthol mix of oils I keep close, to redirect my brain impulses to the areas that process freshness, and the gift of hinu kawakawa from a dear friend, chamomile and lavender, to give calm and rest. Every moment during treatment when I felt a bit gross, I just rubbed the oil all over my wrists and under my nose. The more the better. And it works.

If anyone is reading this has regular appointments in the day unit and similar aversions - message me, I can send you something x

Daphne Odora

By Sandra Turner

Daphne Odora grew profusely at the front verandah of my grandmother’s home but by the time we had shifted to the big house, the plant had died and had been replaced by something very nondescript.

Shifting to the homestead signalled a change of the guard.

With my grandmother now living in the neighbouring town, my parents were able to claim full ownership of this family farm, although it would be many years before Alice gave up her proprietorship of the garden.

Pruning the fruit trees or shifting an established plat could hardly be achieved without her critical witness.

The garden of my childhood can be found in small snatches of my own garden, though if you are looking for the large sweeping lawns or the perennial borders you may well question my claim. No, it is the smell and shape of individual flowers that are the fingerprint of my childhood. Lilac, clematis, double ruffled daffodils from the orchard, grape hyacinth, and of course daphne odora - all known to me as old-fashioned flowers, simply by virtue of having been in my grandmother’s garden.

My other grandmother, my mother’s mother, grew Livingston daisies. They really were her one and only flower. Each year she planted them up the pathway to her house where they sat snug against the earth, opening up to any beckoning warmth.Their brightly coloured faces never caught my imagination but for my mother they continue to live on in her garden. The flowers that work best for me are those that can be picked and they must be scented. Roses without a scent are a cruel dupe.

Daphne odora, an ordinary looking plant, gives little indication of her powerful scent. The fingers of her perfume deftly stop you in your tracks, demanding that you find her source and drink your fill. I know there are many places in my garden that she would flourish and be enjoyed but it was with a tight heart that I planted her not far from our dining room doors. Next Spring seemed a long way off and I had no confidence that my health would hold and that in another four months I would have enough stamina to walk easily around my garden. Radiotherapy had left me exhausted beyond all measur and without any of the usual surety for knowing myself.

Some six seasons have since passed and daphne odora is well established in her bed. This year she was her most glorious, robust enough for me to dare to take some sprigs from her.

The fingerprints of Alice’s garden are easily found in mine if you know the clues and are not looking for the obvious. What you do see in my garden are the 70+ rose bushes, gloriously scented and hued across the spectrum of crimson to lilac and deep red, through to all the pinks and everything else in between. I wonder what unexpected sign’s my children’s children might find of their grandmother in their lives?

Endnote:

On the concept of empty land, “wilderness” and “harsh” places to live:

I want to make a few critical points about what I’ve said about Alaska and my experience there. The first is that though I did not thrive in Alaska, evidenced by even this small exploration into my inability to smell, Alaska is thriving. And many people thrive in Alaska. The lack of smell felt like a type of sensory deprivation to me, and I most definitely had seasonal affective disorder, but Alaska is a place of vibrancy and life, within the both the winter and the melt, into the short spring, summer and autumn seasons, when the animal and plant kingdoms are ecstatic with life. This may seem trivial, but I say this because to call Alaska barren or a wilderness, even in the case of smell during the winter time of rest, is a type of modern day colonialism: to be blind to the life that exists there even through the winter.

The concept of “wilderness” is truly problematic, and has been and is currently being weaponised in myriad ways. In the mid 19th century, the concept of “wilderness” was created as a way to take lands from Indigenous Peoples and turn them into National Parks. In many cases, the land had to be made uninhabited, first. And we know what that means. In Alaska, Alaska Native seasonal hunting and fishing areas were used as dumping grounds for radioactive waste post WW2, apparently justified by the belief that they were uninhabited, and therefore fair game. Spoiler alert, my dear reader, they were not. Alaska Natives were also subjected to radioactive testing (something I heard of first hand, by an Elder I was working with on the ice who was a test subject), to understand how they could be so tolerant to cold temperatures. To add to these modern day atrocities, in the 50s and 60s, the British Army used Kiritimati (Christmas Island - Kiribati) as a nuclear weapons testing site during the Cold War. “Local people were forced from their homes, at best; or were left in place potentially to be exposed to ionising radiation, at worst.” These are but a few examples.

For Alaskan history, the arrogance of the US Government, and the makings of the first conservation movement, please read the Firecracker Boys, by Dan O’Neill. For more on the way “wilderness” was weaponised and created for the taking of Native lands, see Time’s The Story We've Been Told About America's National Parks Is Incomplete by Dina Gilio-Whitaker. For information about how the British Army has violated the Kiribati people, and continues to do so with the horrific cancer rates they are now suffering, see The atomic history of Kiritimati – a tiny island where humanity realised its most lethal potential, by Becky Alexis-Martin

Again, powerful and moving Kate.

You in-still a deep thoughtfulness in me, as your Mum did. Xx

Wow, Kate, what amazing experiences you’ve had! I don’t think I knew about your time in Alaska. Those are fantastic photos too. Thank you for sharing! xx